Introduction

Martin recently reviewed Lomo’s replica of a Petzval lens. I commented, perhaps slightly snidely, that vintage Petzval lenses are still around, often for less money, and often with better centre sharpness – and certainly with a vast choice of models and thus rendition nuances.

Martin suggested I share my knowledge in an article. And like an inverse Spice Girl, one became two. This one seeks to introduce you to the weird magic of Petzval lenses and their widespread availability from old cinema film projectors. The next will look at adapting them, and indeed any old projection lens, to a modern-day camera.

So here we go, I guess.

All pictures were taken on full-frame evils: a Sony a7r2 and an a7cr. Some were cropped; all were adjusted for proper blacks and whites according to ancient darkroom principles. None had additional sharpening or aberration correction applied.

Sample Images

Contents

Disclaimer

This is an article by one of our readers, Mark, who kindly wanted to share his vast experience on adapting projector lenses, mostly with a Petzval design. All pictures are taken by Mark—design and layout of the article is by Martin.

//Martin

If you like the Lomo, get it! They actually make a whole range of Petzval lenses and currently have a 35/2, 55/1.7, 80.5/1.9, 58/1.9, and 85mm f/2.2, in reverse chronological order. (Only) The latter two will also fit SLRs, and use Waterhouse slot-in aperture disks instead of inbuilt apertures like the rest. ancient-optics.com even makes cine housed versions.

I respect what Lomo does, and I know that doing it in small numbers entails higher per-piece costs. I also hugely respect how they moved away from the cheap plastic crap company they were a decade ago, to proper quality materials. Their new lenses are even made by a proper camera company (well, of sorts): Zenit.

But why improve what’s already perfect?

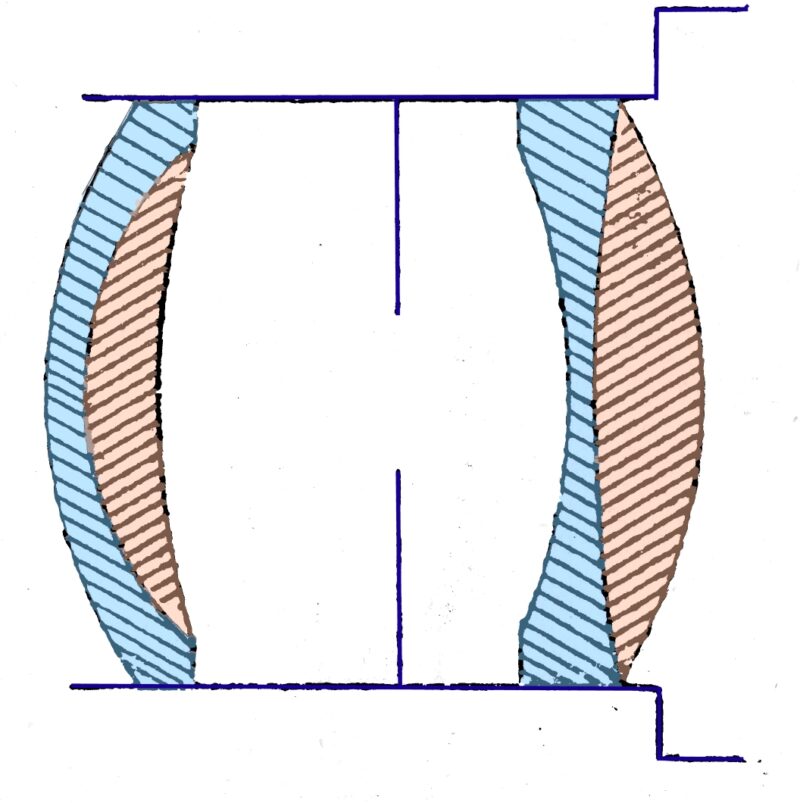

What’s Petzval Anyway?

The Petzval look has seen recent appreciation for its creative signature of swirly bokeh and blurred image edges. Originally, though, those were just a byproduct of an 1840s endeavour to create the then-fastest lens for portraiture without motion blur, and without the reams of spherical aberrations (glow) that fast yet simple approaches like a meniscus gave. In fact, a Petzval design has no glow to speak of, and in 1840 had the staggering speed of f/3.6! Moreover, it’s a simple optical design of two doublets, but with high speed and high centre sharpness.

This made it ideal to be taken up later for, among others, 16mm film projector lenses that needed to be cheaply mass-produced for schools and the like, yet needed to be fast to attain decently bright projected images, as the alternative, stronger light bulbs, would produce excessive heat and increased fade of the film’s colour dyes. But since Petzval lenses are only sharp in the centre, for use in film projection where creative blur is not desired, they need a comparatively huge image diameter. A 16mm film frame is less than half the size of micro43, which in turn is a quarter of full frame. Yet many 16mm projector lenses illuminate full frame – if you’re fine with all the swirl and blur. But if you’re in the market for the Lomo replica, then you’re not only fine with swirl and blur, you’re LOOKING for it.

But if you’re in the market for the Lomo, you’re probably also open to creative experiments. Then you owe it to your artistic expression to have a little look around at some of these historic film projection offerings.

The 1840s photographic Petzval lenses were designed to illuminate large-format glass plates. That entailed focal lengths north of 100mm, which are impractical for the much smaller full-frame and GFX formats of today. Moreover, these smaller formats would only use the centre of the illuminated image, thereby forgoing much of the now-desired swirl and blur. Those mostly reside in the image edges.

On the flip side of swirl, there ARE NO sharp edges with a Petzval lens, at least if using all or most of its illuminated image circle. The Lomo lenses are no exception. However, that holds a massive boon for separation: a 50/1.4 Petzval lens delivers easily as much separation as a conventional 50/1 lens! Mind you, there is a huge difference in the rendition character!

Still, if you value the centre-midfield-corner sharpness tests we’re usually blessed with on this website, you might prefer a conventional lens.

And don’t think you could stop the lens down for added corner sharpness. Projector lenses don’t offer an aperture. Projected film, even at full aperture, is so dim as to always require a subdued, if not completely dark room. There’s no need to REDUCE light further. There’s also no need for more depth of field when projecting onto a flat wall. Designing a lens with decent corner-to-corner sharpness for the intended projection film format was good enough.

Choosing a lens

Perhaps you’re wondering: Can we just use any projection lens as a taking lens?! To quote someone with a Nobel prize: Yes, we can. Because the great thing about light, very much as opposed to the national rail service, is that it does not care which direction it travels.

Mind, though, that whether it MAKES SENSE to use a specific lens is quite a different story.

Specifically, there are two technical criteria to observe, outside of personal taste: Image Diameter and Back Projection Distance. Sounds sexy.

Image Diameter

As a rule of thumb, when choosing a lens, the shortest focal length likely to illuminate your target camera format is equal to that format’s diagonal.

Say what? 36x24mm full frame has a diagonal of 43mm. So, most projector lenses of more than 43mm focal length should illuminate an image diameter that more or less covers the full frame image. 35mm focal length lenses usually will not. However, a bit of research is still advisable. Many, especially fast, 50mm projector lenses, still only cover the obsolete APS format.

Back Projection Distance

The space between the rear glass of the lens and the plane where the lens projects a sharp image is the back projection distance (BPD). It has nothing to do with a lens’ original use in film projection! It is instead similar, but not equal, to the more common concept of flange distance, but there is no flange here.

BPD varies for every lens design, and typically grows with focal length. Whilst this also applies to the glass in systemised lenses, i.e. Canon FD or Leica M, the lens barrel designer has already compensated for it and made the resulting lens fit the system. When adapting projector lenses, WE are the barrel designer.

A medium format SLR like a Hasselblad puts a lot of mirror, and thus distance, between the rear lens and the film plane. A lens’ BPD thus needs to be fairly long to overcome it and still focus on faraway subjects. This is usually only given in longer focal lengths of 100mm and more. Ideally, you want infinity focus, meaning a sharp image of any subject, regardless of how far away, even the moon. Practically, you might be fine with a 2-3m maximum focus distance for portraiture.

A fullframe SLR has a smaller mirror and thus requires less space, typically working with focal lengths below 100mm. An Evil has no mirror at all, hence often called mirrorless, and so requires even less space. It works with most 50mm lenses. The Nikon Z system shaves off another 2mm compared to Sony FE and Canon R Evils. Whether 2mm makes a difference depends on what you do with it (am I right, ladies?), i.e., which lens you want to adapt.

If you already own the intended lens, hold it to your camera and focus on a faraway subject. If there are a few centimetres between the rear lens and the camera, all is well. If not, it’s either gonna be a tight squeeze or a no-go.

If you don’t own the lens, know that the most famous lenses are documented. For a first foray into adapting non-photographic lenses, stick with well-documented ones to ease your process (and wallet). Research if someone has adapted your desired lens to your intended camera system – and if they managed to focus on anything else than close-up flowers. If so, all is well.

Projection Petzval Recommendations

For the most intense Petzval swirl effect, you want the shortest focal length that still covers your camera format (and allows for proper focus). On a full-frame Evil, that is usually 50mm. If you intend to crop your full-frame image to a different aspect ratio, like 1:1 square or 1:3 panoramic, you might get away with slightly wider focal lengths. You can also go the vintage route of ROUND images and just use whatever image circle a lens gives you.

Here are some recommendations for Petzval-type projector lenses with both full-frame-friendly focal lengths and decent availability:

The Meyer Görlitz Kinon Superior series is the classic and by far the cheapest. 50mm and longer focal lengths cover full frame; the much rarer 40mm virtually does as well. The 65mm covers GFX. There are two series: one without any quoted speed – it is in fact an f/2.2. And an f/1.6 series. The unquoted bread-and-butter 50mm goes naked (unmounted) for under 50€ and is the sharpest Petzval projector lens I have used. The 50/1.6 is rarer, more expensive, nearing 300€, and much softer, but its rendition is closer to the legendary Meyer Kino Plasmats than the f/2.2s. Note that all are pre-WWII lenses and thus denominated in centimetres, i.e. 4cm, 5cm, 6.5cm, etc.

The Zeiss Kipronar series was Zeiss’ cheapest line of projector lenses. Only 70mm+ covers full frame. Sharpness is between the two Meyer lines; image quality is further reduced by a hearty dose of both chroma and spherical aberration. They are also rarer and often abused, only worth the extra if you prefer their rendition.

Emil Busch of Rathenow (later Rathenower Optische Werke or ROW) made a series of f/1.6s called Neokino. The 50mm more or less covers full frame, but is quite mushy. The 65mm covers GFX.

Schneider of Bad Kreuznach, Germany, and their subsidiary ISCO of Göttingen (“Josef Schneider Company”, established by the great Albert Tronnier) made the Kiptar series. Their look is more subdued. Note: the SUPER Kiptars are not Petzvals.

The original (Soviet) Lomo company made the P series: P-4 are uncoated primes of 90-150mm and f/2. P-5 are coated and extend to 180mm. P-6 extends the speed to f/1.6. I have not used them, but they are well-documented, so I’ll link to them below. Thanks to the EU’s Russia sanctions, they are harder to find today – another misguided policy that hurts EU citizens instead of Putin, much like the petrol embargo. But you might find them from Ukrainian sellers, and importing from there is customs-free.

Bausch & Lomb made the Cinephor series, exhibiting a slightly subdued swirl. Most will need to be imported from the US. Note: the SUPER Cinephor lenses are Double Gausses.

Bell & Howell made a series of f/1.6 and f/2 projector Petzvals, with focal lengths denominated in Americanish, i.e. 2” for 50mm, 3” for 75mm, 4” for 100mm etc., but they are quite rare and expensive.

Cindo of Paris made a few as well, with bokeh rendition closer to more conventional lens designs and sharpness that is, euphemistically put, disastrous. I’ll leave links below.

Then, there is the Kodak Cine series of f/1.6s, but the 50mm barely covers APS! There’s the Max-Lite series by the famous Dallmeyer (of London; no relation to Meyer Görlitz). There’s the really nice Astro Berlin Kino Color IV series and the creamy Benoist Berthiot Cinestar series. There is also the Ampro Simplex series of f/1.6s, but with a boring rendition.

Finally, there is the Angenieux Type 86 series for if you REALLY wanna burn some cash. It is known as the fastest Petzval, at f/1.5, paling any Lomo.

And for some giggles, look up the ROW Cinerectim (as opposed to the Cinerectum, which I suppose is what you get when you watch too much TV).

If you want to dig into historic photographic Petzvals, the list seems endless. Voigtlander, maker of the very first serially produced Petzvals, is an expensive and rare starting point. More exotic names include Darlot, Hermagis, Laverne Paris, Pathé, Holmes, Liesegang, Taylor Hobson’s Maximum and Ultimum series, Ross London, and Laack’s Heleston and Schnellarbeiter.

What Else is There?

This might be the right moment to note that by far not all projector lenses are Petzval designs, but that other types of projector lenses give equally characterful images, albeit with very different signatures.

Plus, as with all historic lens designs, the variations over time are endless. (Ever got into a discussion as to what is a Double Gauss lens, versus a Double Gauss derivative, versus a Biotar, Planar or Xenotar?) Kodak, for example, patented 6-lens Petzval designs after WWII.

My own favourite non-Petzval projector lens is the Meopta Meostigmat series from a country that does not even exist anymore, Czechoslovakia. The 50/1.3 virtually covers full frame. The 50/1 and 35/1.3 only cover APS, but the latter has, in my opinion, the nicest bokeh of any lens. They also made a very fast 70/1, but it too only covers APS.

Zeiss made the Prokinar series as a one-up of the Kipronar. Not a Petzval design, but characterful. Even its 50mm covers full frame.

The professional Visionar series, initially made by Rathenower Optische Werke, which Zeiss later took over, is also not a Petzval design and much tamer. The 90mm still vignettes on full frame when focused to infinity.

Kowa’s Super Prominar series of projector lenses are also worth a mention. Note, though, that Kowa named just about anything Prominar, so your search might get confusing. For full frame, you want the 50/1.3; the 50/1.2 only covers APS.

There’s the Philips Philar series of triplets; there’s the Isco Duotar series, and the LZK (“Łódzkie Zakłady Kinotechniczne”) Polkinar series, as well as the creatively-named Optical Proiectar (sic). There are several Rodenstock series, but I have not seen one covering full frame at focal lengths below 100mm.

And if you want the cheapest Angenieux lenses in the world, look for the Angenieux Kodak Anastigmat series. It’s still got some lovely bokeh, but it goes for under 50€.

Optical Performance

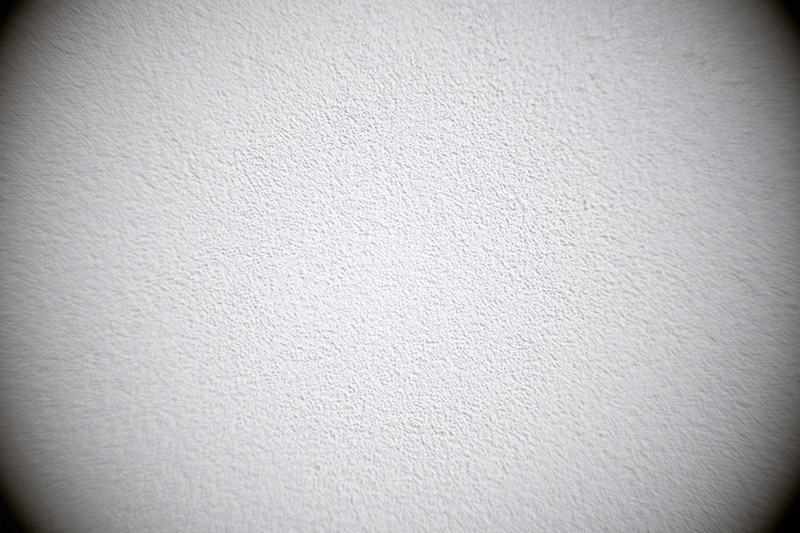

Sharpness at Infinity

Test Scene

Centre Sharpness

Medium Distance Sharpness

Here we show the test scene first to give you context and a sense of the lens’s character, followed by 100% crops from the centre of each image.

And now the 100% crops of the centre of the images:

Vignetting

Conclusion/s

I heartily recommend looking into such left-field vintage lenses like obscure Petzval remnants. They broaden any toolkit for creative expression and provide both a much vaster choice than off-the-shelf products, as well as image character signatures that no lens optimised for regular photography does.

How Is It Done in Practice?

Would you like to see how Mark converted the lenses and maybe learn how to do it yourself?

Leave a comment if you’re interested — if at least five people are, we’ll make an article about it.

Photographic Alternatives

If adapting sounds too complex (it really isn’t), you’re likely to find people online prepared to do it for you. An inquiry in some user forum might yield results. Yet, let it be mentioned that there are a few commercially available photographic lenses with similar rendition, although most are not TRUE Petzvals. These are also an option if you like the effect, but don’t quite want the full monty.

80/1.5 Helios-40-2, aka the Cyclop (a Soviet 70/1.5 Zeiss Biotar elaboration). It only swirls in a narrow band of focus distance, though!

35/2.8 Lensbaby Burnside and 60/2.5 Lensbaby Twist.

57/2 MS Optics Petz, which is aptly named since it’s not the full Petz-val experience, despite being the only true Petzval design here: it hardly shows any swirl, and quite a lot of spherical aberration. Character bokeh for sure, but no Petzval herald, and very expensive.

And if you like even less of the swirl effect, have the 58/2 Helios-44 (the Soviet’s 58/2 Zeiss Biotar rip-off) or the 4cm f/2 Zeiss Biotar off a Robot.

Sample Images

Links

Treat yourself to this article on history’s fastest projection lenses.

And if you’re interested in the very early Petzval lenses: Look here!

This table lists lens coverage on GFX cameras and includes many projector lenses. It’s also a starting point for full-frame research.

Here are samples and details of the Lomo P series: The 90/2 is here, and the 120 here.

The Cindo Paris offerings are probably not worth your attention, but to quench any FOMO: https://flickr.com/photos/heritagefutures/14200483161 and https://flickr.com/photos/heritagefutures/29824741853

Petval lens diagram: By E. J. Wall scanned by Velela – E.J.Wall, Dixtionary of Photography, Published 1890, Public Domain

Donate

Did you learn something new, find this article useful, or simply enjoy reading it? Would you like to make a donation?

For this article, make your donation to Malcolm Cat Protection Society.

About me

My background is in journalism. Attempting to battle severe, untreatable depression, I immerse myself in picture-taking. It’s a subconscious desire to literally see the world through different lenses and a faint hope of gaining a different perspective on life – with an acute awareness that any picture might be the last. Mark Stein is a nom de plume.

https://flickr.com/photos/hach_und_ueberhaupt

“Would you like to see how Mark converted the lenses and maybe learn how to do it yourself?

Leave a comment if you’re interested — if at least five people are, we’ll make an article about it.”

Yes please!!!

I’ll be honest, I’m not interested in adapting a Petzval, don’t really care for the look… But I’d still be interested in reading the follow article about it, I think Mark did a great job here!

Oops, dunno why this ended up as a comment reply.

No worries…

Still I think its interesting to at least know the procedure, its a very specific look this one

“Would you like to see how Mark converted the lenses and maybe learn how to do it yourself?

Leave a comment if you’re interested — if at least five people are, we’ll make an article about it.”

Absolutely! Thank you all.

Mark, many thanks for this article, I found it really interesting.

Please could you write the follow-up article you suggested, about how to convert projector lenses to use on a camera? I would really appreciate it if you could, please.

You can’t just start a topic like this with a such good written article like this, and stop. Please go on!

Excellent article with some very interesting and capable lenses mentioned and of course also fascinating, unique and beautiful images shown! Well done.

Thanks a lot for sharing your knowledge and experience and also thank you for the shoutout to my small “Fastest Projection Lenses” article… it still is incomplete in parts, but I’ll try to update it in the future.

I appreciate your work and would love to collaborate in the future if the opportunity arises!

Very interesting article! I am very interested in the conversion process too!

Great article and a fun read too. I would love to learn about adapting these lenses.

I am very interested to see the adaptation !

I’m from that country that no longer exists and I’d love to read the sequel.

I’d love to see an article about how projector lenses are adapted to “evil”s – i.e. mirrorless digital camera bodies!

A very exciting and entertaining article. Even though I’ll probably never make such adaptations myself, please definitely write the follow-up article!

I’ve considered adapting projector lenses several times over the years, but the guides and articles I’ve read always seemed to lack important details or assume access to parts I couldn’t find sources for. I’d certainly be interested in a follow-up.

Thanks for this great article about a not so common topic. Very well writen and interesting. I adapted myself several projector lenses and I am very curious about the follow-up article.

Totally fascinated by this write up, and would love to learn more about conversion to Full frame Sony!

Great work Mark, exactly something I was looking for a long time! Can’t wait to see the second part!

Nice article and examples. I also would love to see how this was done.