With the growing interest in analogue photography, as Bastian so inspiringly explores in his Analogue Adventures, I too have decided to create a series of film-related articles. I’ve chosen not to use the same title, as my own relationship with film photography goes back to a time when it was simply photography to me. While Film Photography would feel like the most natural title, I’ve decided to go with Analogue Photography instead, to keep a sense of continuity with Bastian’s series.

To offer some context, let me take you back to where it all began — a journey that, I suspect, may feel familiar to others who started their photographic path around the same time I did. If that’s you, chances are you’ve also been around long enough to remember when film wasn’t a choice, but the default.

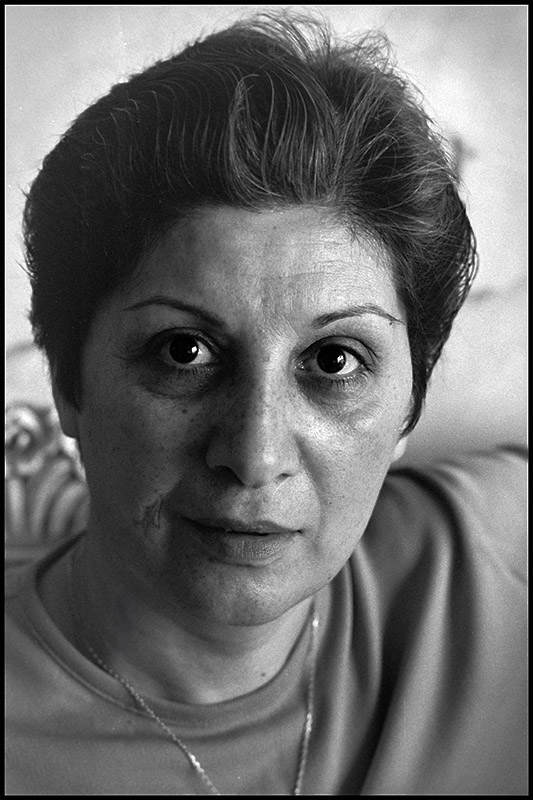

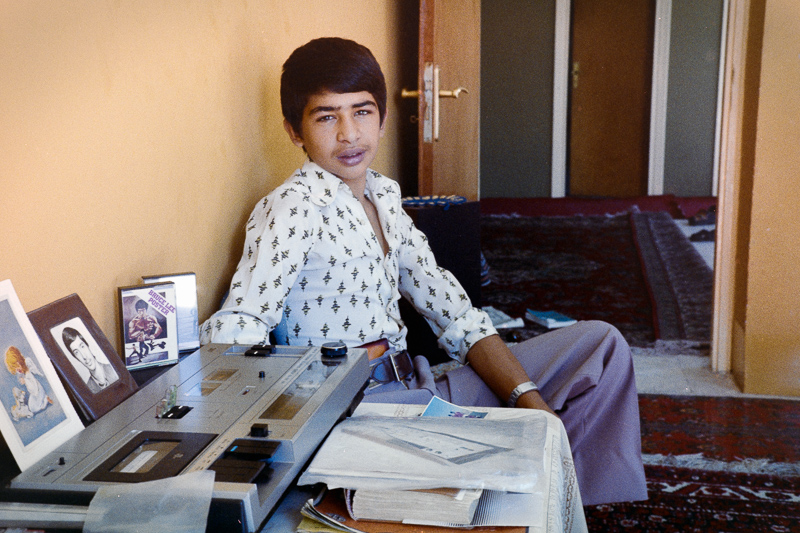

As a young teenager in the late ’70s, I developed a growing interest in drawing and pictures, which led my parents to give me my first camera — a simple point-and-shoot 110 camera. At first, I was thrilled just to have a camera of my own — but after shooting two or three rolls of film, I began to notice its limitations. After a year—and a good deal of persistent nagging — my mother bought me a much better 35mm rangefinder camera with manual adjustment possibilities and a fantastic fixed 40mm f/1.7 lens. The difference in image quality was striking — I could finally capture the world the way I saw it. A lot of friends and family photos were taken over the next couple of years, all on colour negative film — that was simply what everyone used back then for family photography.

I became proficient enough that even some relatives asked me to photograph their children’s birthday parties and, eventually, even a wedding — which, thinking back, was quite remarkable for a kid still in his mid-teens. Then again, they were probably just trying to save money.

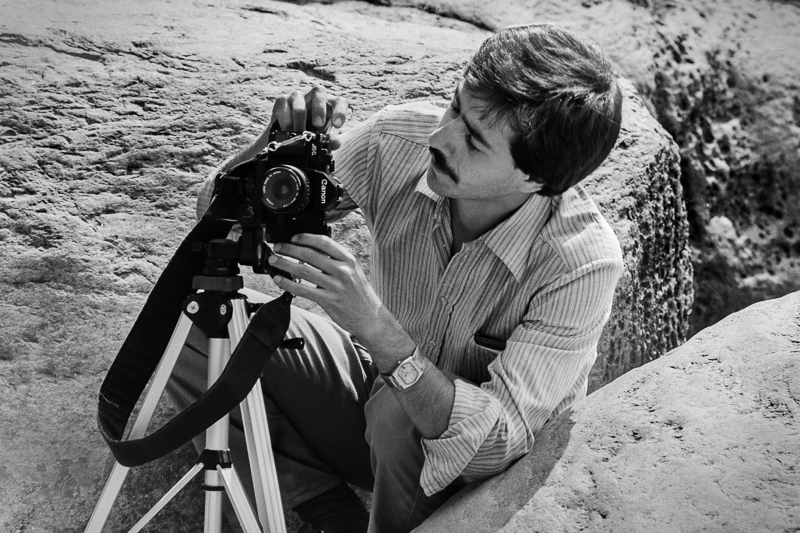

During my late teens, my interest in photographing more than just family and friends really began to grow. I took on summer jobs and carefully saved both my earnings and pocket money to buy a used SLR camera, along with three lenses: a standard 50mm f/1.4, a 28mm f/2.8 wide-angle, and a 135mm f/2.8 telephoto.That’s when I truly began to learn the fundamentals of photography — experimenting with depth of field, composition, light, and a variety of films. I tried different brands and film speeds, mostly color negatives, which I had developed and printed at local photo labs.

But now that I was taking photography more seriously, I began to notice things I had previously overlooked. The results were often inconsistent — colors would sometimes shift, prints came out too light or too dark, and occasionally the tones looked washed out, possibly due to overused chemicals in the lab. It was a nightmare because you could never be sure where things had gone wrong. Had I exposed the film incorrectly? Was the lighting off? Were there any issues with the film’s colour balance? Did something go wrong during development or printing? Or was it just a different kind of paper this time? The learning curve quickly became long and steep — not to mention expensive.

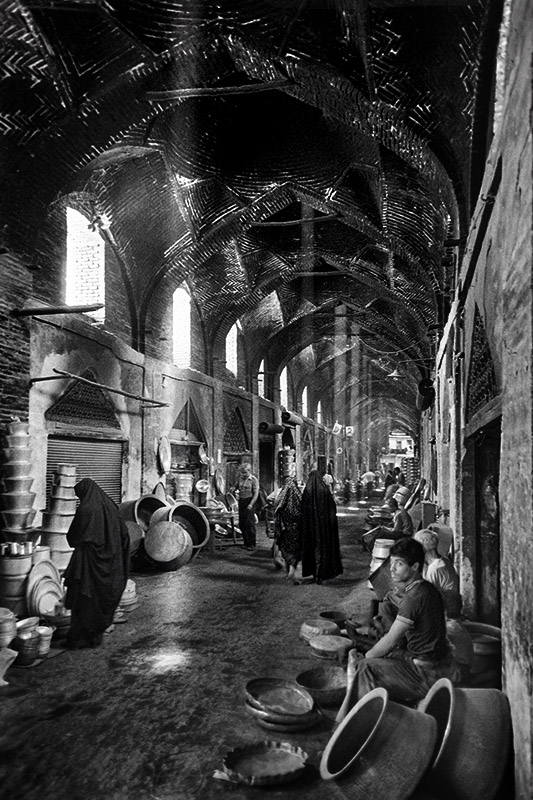

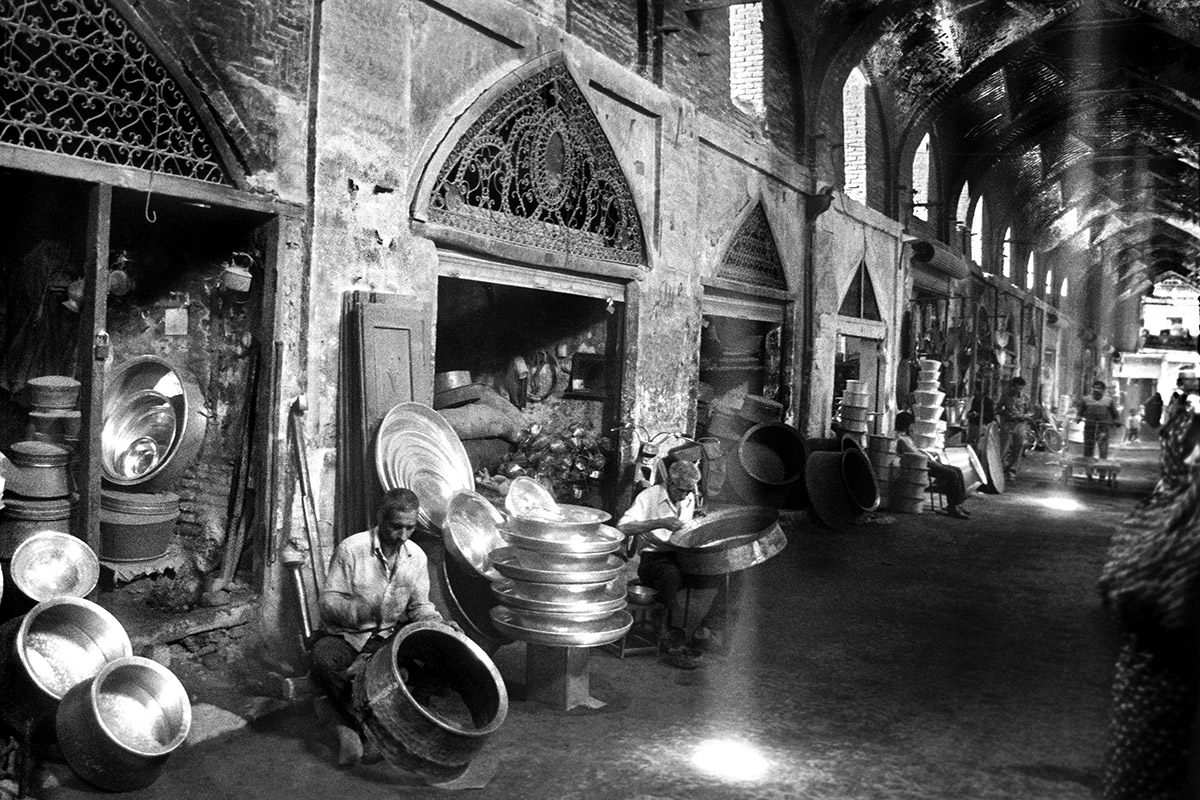

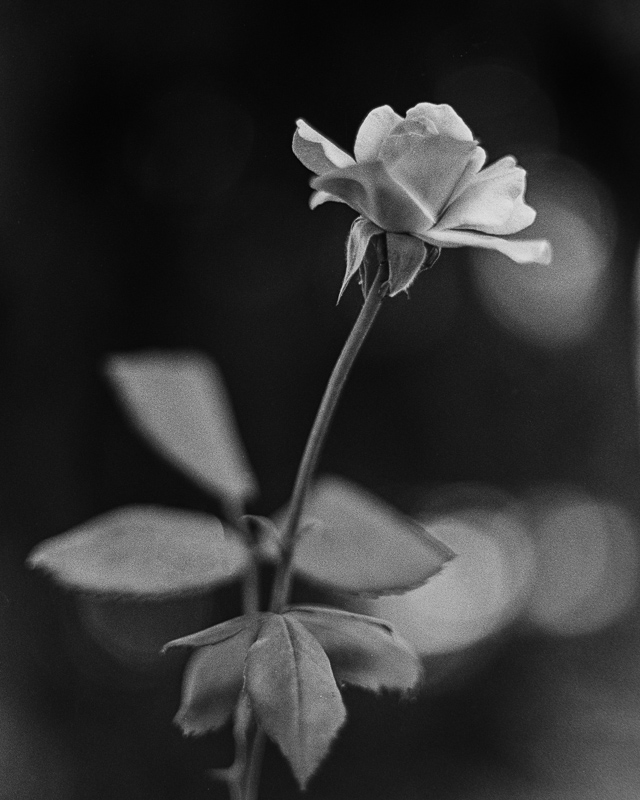

At the same time, I began reading photography books and studying the work of the old masters, which opened my eyes to the expressive potential of black and white photography. With the help of those books, and advice from a few seasoned photographers, I realized that to achieve consistent results that matched my vision, I would need to take control of every step of the process — not just choosing the film and taking the pictures, but also developing the negatives, enlarging the prints, and selecting the right photographic paper.

At the time, colour photography was often seen as suitable mainly for snapshots, while black and white carried a more serious, classic reputation. The fact that many established photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe, Jerry Uelsmann, and Sebastiao Salgado, among others, continued to work exclusively in monochrome further shaped my thinking. I remember reading that even after William Eggleston — one of the pioneers of colour photography — had his groundbreaking 1976 solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Henri Cartier-Bresson reportedly told him at a dinner party, “Colour is bullshit.” That, combined with the earlier-mentioned challenges of working with colour, ultimately inspired me to switch to black and white and learn how to develop and print my own photographs.

I bought several books on the subject and teamed up with a friend who shared my growing passion. They had the space, so we built a home darkroom in their basement, which I was also able to use.

For many years, I developed and enlarged my own black & white negatives, the first year or two always in that friend’s basement — a time when home computers were still unheard of and far from anyone’s everyday reality. I spent so many hours in the darkroom that his family eventually gave me my own key, so I could go there even when he wasn’t home. Sometimes his mother would come down with a sandwich, saying I must be hungry, and I even ended up sleeping over there occasionally. Gradually, I got better — not quite an Ansel Adams or Cartier-Bresson, but I had reached a level I felt content with. At least, that’s what I thought at the time.

Over the years, I’ve come to realize that not only was I far from fully mastering black & white photography, but also — looking back — I now see just how impatient and careless I could be. In particular, I rushed the fixing and, even more so, the washing of my negatives. At the time, they looked fine, and I didn’t think much of it. But over the years, that impatience has come back to haunt me. Many of my negatives have deteriorated, with tiny spots where the emulsion has lifted or disappeared entirely. So, here’s a piece of advice, if you develop your own film: be really thorough with the fixing bath and rinsing your negatives. A few extra minutes and a couple more liters of water now can save you from a lot of anguish and regret later.

Still, the temptation of colour had always bubbled inside me…

To be continued…

Affiliate links:

Do you need to buy films? Go to Amazon!

Do you need to buy anything? Go to Amazon!

Do you want to buy used gear? Go to eBay.com, eBay.de, eBay.co.uk!

Further Reading

- Analogue Adventures – Part 1: Choosing a Camera

- Analogue Adventures – Part 2: First Roll of Film

- Analogue Adventures – Part 3: Getting things fixed

- Part 18: Choosing a secondary Camera

What Did I Use to Digitise My Slides and Negatives

I have received many questions from the readers about what I used to digitise my negatives and slides. So, here it is:

- Duplicator: JJC Slides and Film Negative Copying Scanning Kit ($95)

- Lens 1: TTArtisan 100mm F2.8 2X Macro (from TTArtisan), from Amazon ($339)

- Lens 2: Pergear 60mm F2.8 MK2 2X , from Amazon ($169)

- Camera: Nikon Zf ($1897)

The Pergear lens is cheaper, smaller, and more convenient to use, but it has significant distortion that needs to be corrected in post. The TTArtisan lens doesn’t suffer from that distortion and has almost no vignetting. However, it’s more expensive and, due to its larger size and weight, less convenient to handle. Both lenses are extremely sharp.

Support Us

Did you find this article useful or did you just like reading it? It took us a lot of time and money to prepare it for you. Use the Donate button to show your appreciation!

![]()

(Donations via Paypal or bank card)

Martin

Latest posts by Martin (see all)

- Review/Comparison: Nikon NIKKOR Z 35mm f/1.4 (vs. 35/1.8 S) - February 8, 2026

- REVIEW: TTArtisan 14mm f/2.8 - February 1, 2026

- REVIEW: Meike 85mm f/1.4 FF STM - January 18, 2026

I like those warm black and White photos. Remember some b&w negatives printed on Ilford’s fiber based paper.

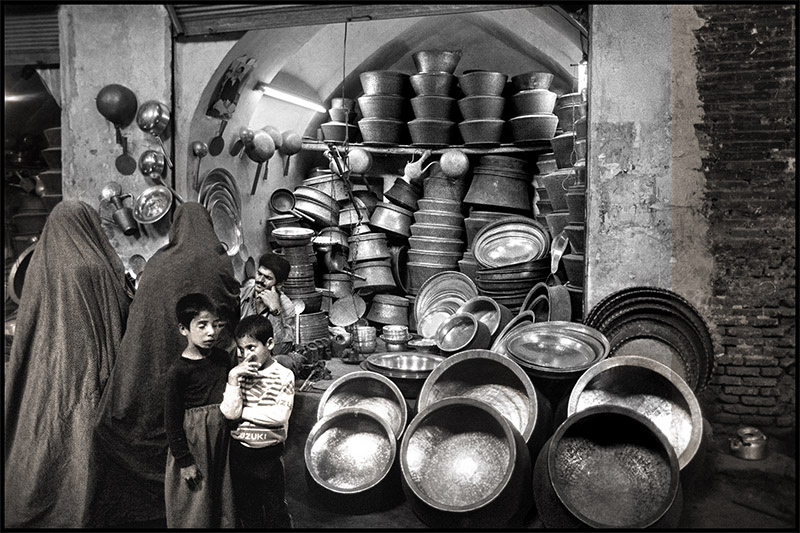

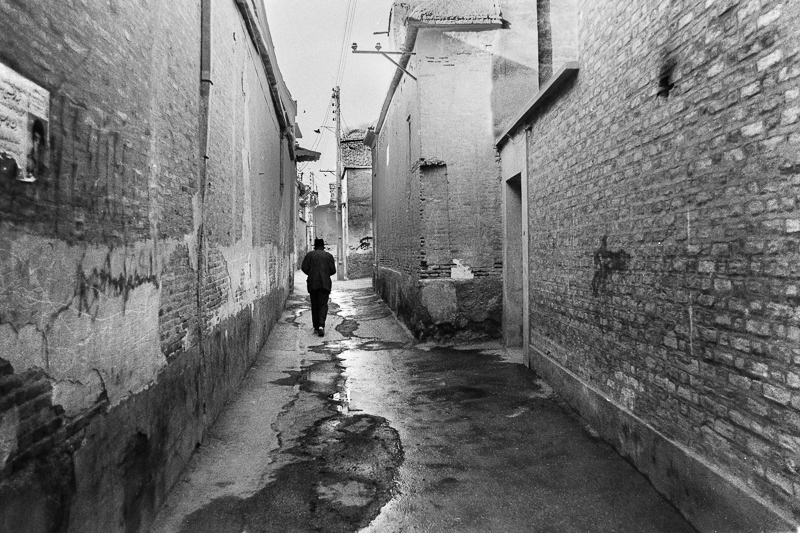

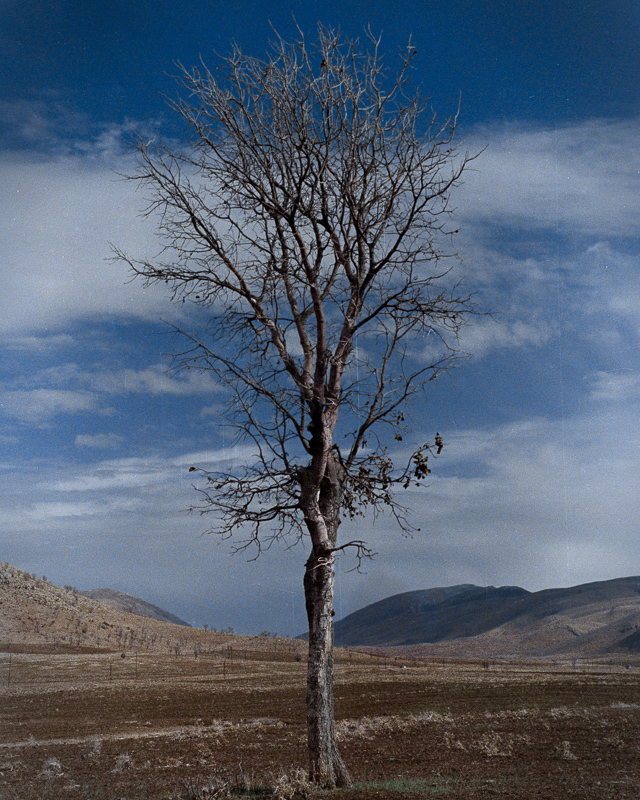

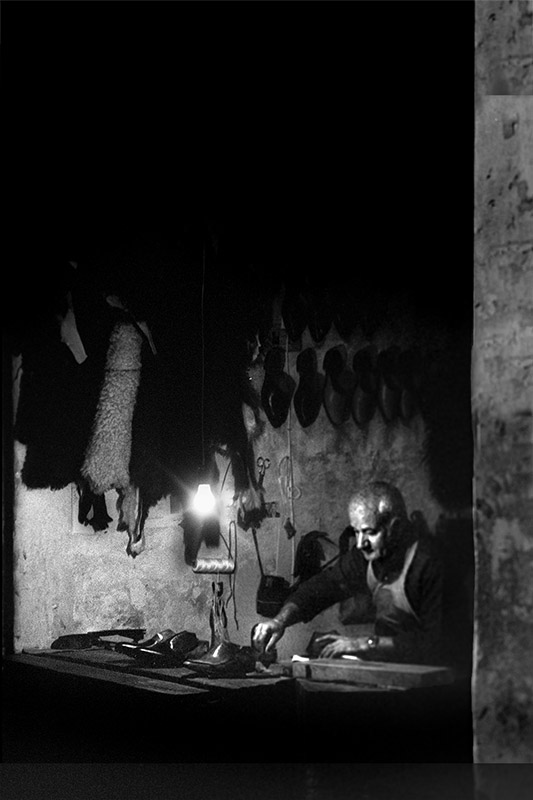

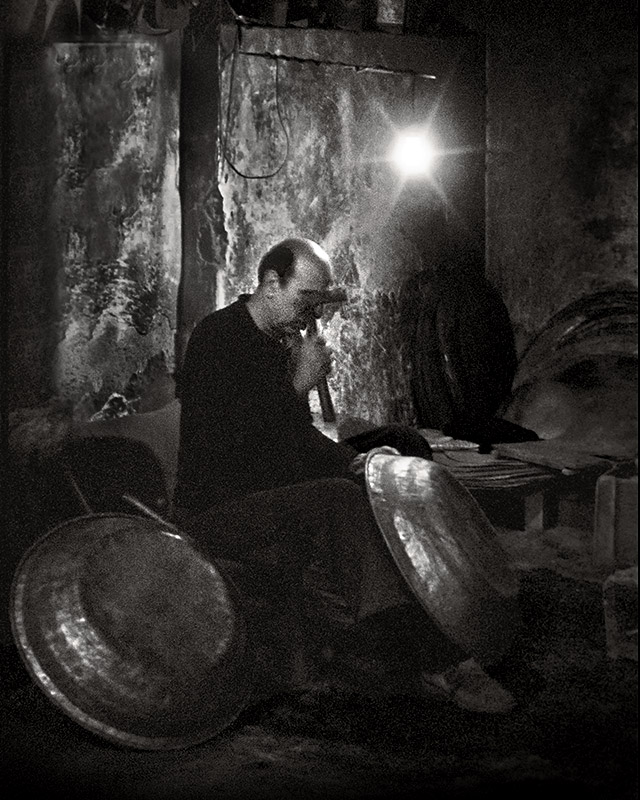

Thanks Martin… I recognize that many photos are from Iran, a country where I have travelled twice and which I love!

Yes, almost all of the pictures from that time is from there.

I resumed using analogue about five years ago. The realisation that I could take control of the whole process was a huge moment. Aside from everything else related to controlling the process, it also meant such a huge drop in costs that I could now bracket if unsure of the light, and generally experiment with more freedom. there is also a more direct line between experiment and result. It leads to greater intentionality.

Development is also fun in its own right.

Wow so cool, very pre 1950 vibes. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for a fantastic trip

Interesting images, thanks for sharing.

Some stunning pictures! Looking forward to see more in the upcoming parts!

This is also a great reminder of how easy things are today: 400 ISO was already a fast film, and it took weeks to see you picture!

Whenever someone complains about image noise at 12800 ISO in their digital camera, I recommend a look at these pictures, and how Martin and other dealt with it…

Great article! I too was a teen in the 70s and film was the only option! I remember thinking that we had reached a peak technology wise regarding cameras! How wrong I was!

I’m interested to know why the shot of the cat taken on Tri-x has grain more akin to Tmax 3200! I certainly don’t remember my Tri-X bung that grainy!

I am not entirely sure, but I think it’s because it was underexposed, most likely due to the sky in the background.