Hi David, can you tell us a little bit about your background and why you use manual lenses?

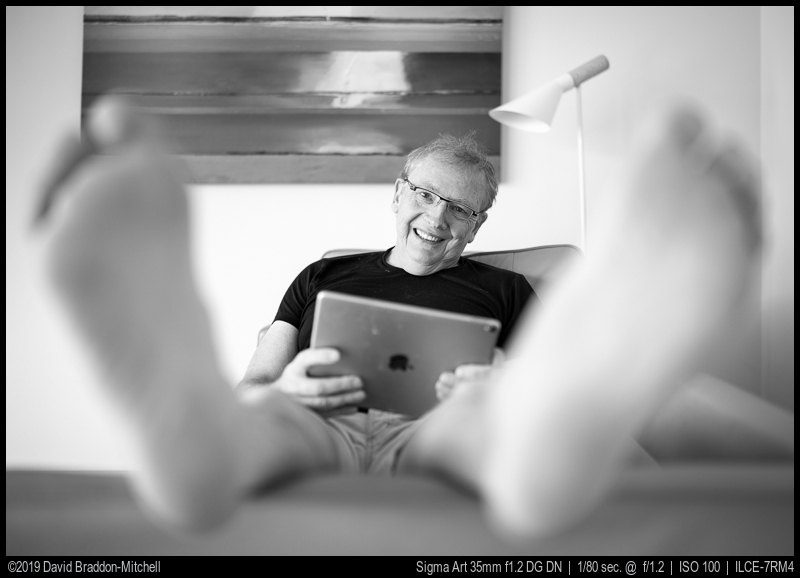

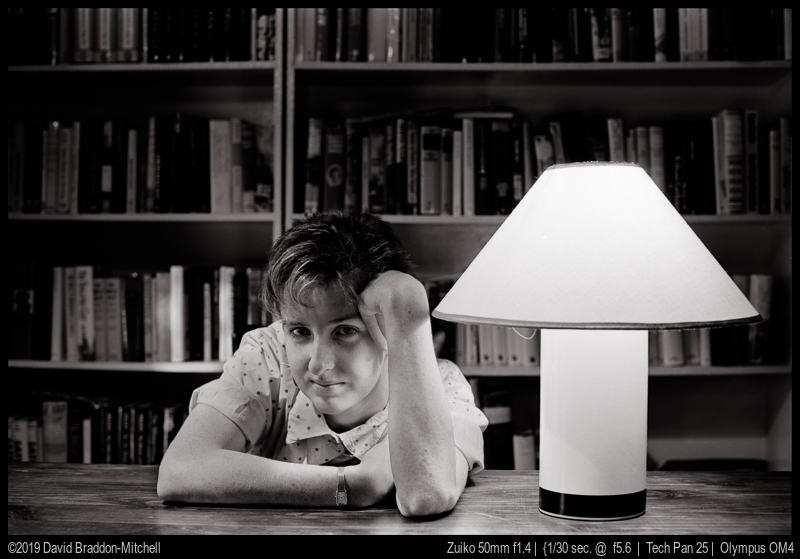

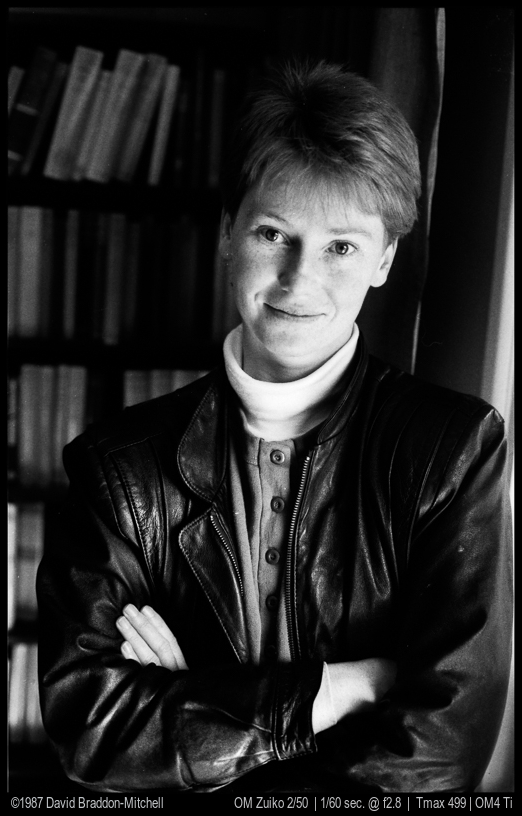

David: I’m an academic philosopher at the University of Sydney in Australia. I’m not sure where I’m from: I grew up in various South East Asian countries as well as in Melbourne (were my family are from) and Canberra. You ask why I used manual lenses: not sure. I can give you a story about that, but I’m not always sure that the explanations we give for our decisions are correct! One reason is likely to be nostalgia. I got into photography when I was a postgraduate student, and quickly became passionate about it. I spent my evenings in my tiny home darkroom (to the chagrin of my partner at the time) and used mainly Olympus OM series SLRS (and some medium format). Those small, beautifully made OM lenses were a pleasure to use and I guess that pleasure is something I feel in the best modern manual lenses as well. Here’s a image from the 1980s taken on the almost grainless Kodak Tech Pan monochrome film:

But that’s explanation, not justification. As for why one should use manual lenses, that’s different. For landscape, and other static subjects, I think manual is better: focus is less likely to shift accidentally after you have set it, and (these days with magnification) it’s actually more accurate than AF. If you are going to use manual focus, then the haptics of a real manual lens beat any AF lens set to manual mode. I never really saw the point of AF for my kind of photography until Sony Eye AF got so good. For wide aperture portraits, eye AF is now wonderful: so I have AF lenses for that application, but that’s really the only time I use AF. The other reason for shooting manual these days is that manual lenses of extremely high quality are often smaller than AF lenses of similar quality. This is partly technical, and partly a cultural or marketing thing. The technical side is just that adding AF adds size, partly because of the need for motors, and because the kinds of designs that you need for the AF to be fast require small and light internal focussing elements, and these sorts of designs are larger. The cultural and marketing element is that buyers of AF lenses tend to think that a good lens is very fast, and that requires size, and they tend to buy smaller slower lenses only if they are budget items. Whereas the manual market contains super high quality slower and therefore smaller lenses, like the wonderful Loxia 2.4/25 which has the best IQ for a lens of that approximate focal length you can get, or the forthcoming APO Lanthar 2/50 which promises to be remarkable.

Can you give us a look into your camera bag and tell us a little about your gear?

David: That’s a tough question. Which camera bag? I am irrational enough (and luckily in a position to indulge that irrationality without too many bad consequences) to own more gear than I need and a lot of bags to put it in.

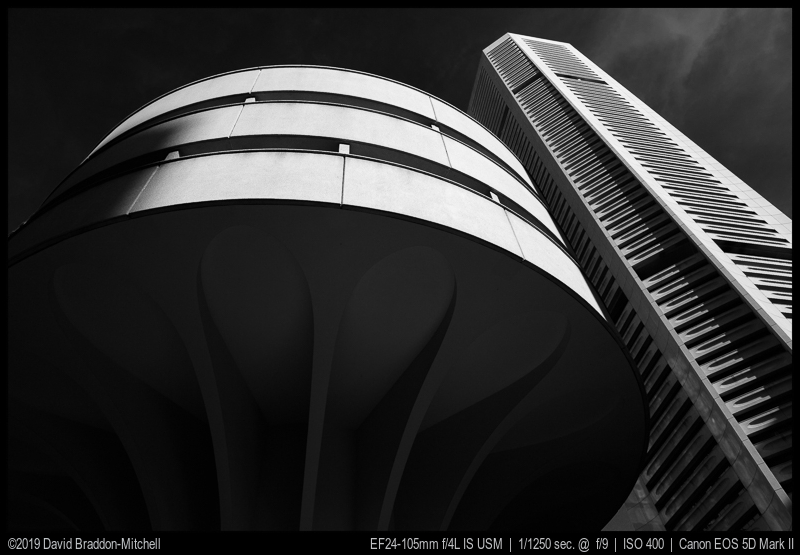

I have only one camera body however: an A7rIV. I’ve followed the A7r series since its inception. Before then I was using Canon 5D series cameras and M43 for hiking:

Before that, Olympus OM film cameras.

I tend not to take much kit with me on any photo session. Frequently just the one lens, rarely more than 3 or 4. Sometimes the kit is determined by the intended subject matter, at other times it’s just a matter of mixing it up: I might take a 21-28-75 kit one day, and a 35-65-110 kit another.

If I had to downsize my kit a little I’d keep a quartet of small manual primes (maybe a set of Loxia or CVs 21, 35, 50 and 85); a decent short tele macro, a 135 (beats a 70-200 for travel) and three fast AF portrait lenses. (say Sigma 1.2/35, ZA 1.4/50, and Batis 1.8/85)

All the pictures in this profile are black and white. Do you only shoot black and white?

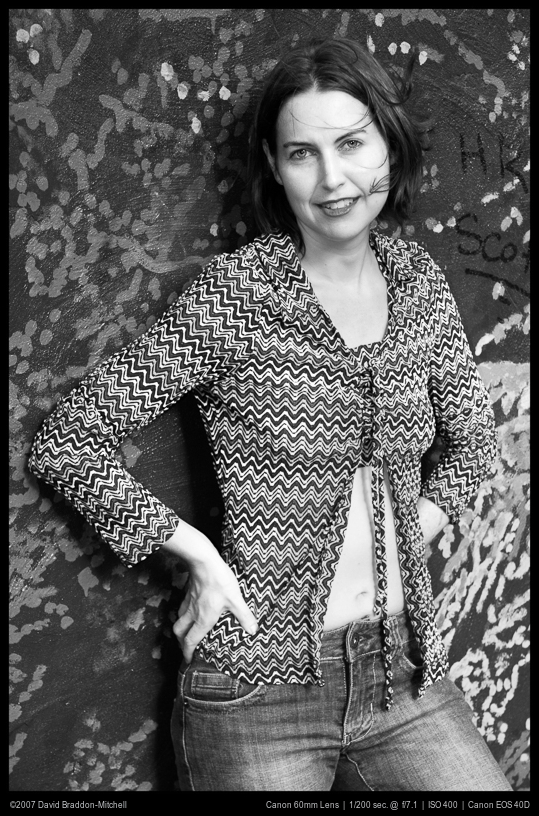

No! Black and white form only a minority of my images, but a large minority. But I love the discipline. Back in the days of film, although I shot colour slides, black and white really was the majority of my shooting. That was in part because dark room work was so much easier with black and white, and to get a final image I loved, I needed to process and print the image myself, and do the sorts of editing that was possible only in the dark room. Of course now Lightroom and PS allow much more even than the darkroom did, so colour can be processed and printed with just as much flexibility. But I still love the special qualities of monochrome photography, and I though for this profile I’d showcase that side of my work.

I generally shoot black and white with the intention of making monochrome images, though occasionally long after I have made an image, I suddenly see that it might work better in a monochrome treatment.

Tell us about your attitude to landscape photography?

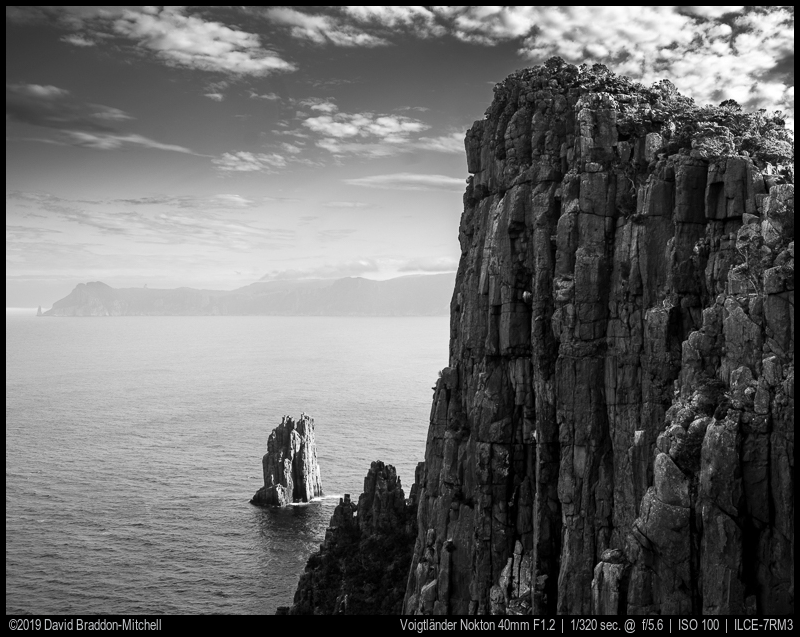

David: I increasingly think good landscape photography is not about attractive images of the land. That’s very easy to do once you are technically accomplished, own an alarm clock, and are prepared to travel. It’s rather about your response to landscapes you know well—it’s the culmination of your own learning and relationship to particular landscapes that you to which you have a rich connection. The next image is of a rock in a wilderness area near where I live, which I visit often and where I have explored all the areas you can see (I published a series of colour images of this rock in On Landscape magazine)

I really came to think this after a recent work trip to Slovenia. Slovenia is a beautiful country, with fabulous opportunities for photography. I had only a couple of days, and didn’t know the place well, so I arranged for a local photographer who runs photo tours to take me privately to a bunch of places from dawn to dusk. He was great, and I had lots of fun, and one sense I was very happy with the images. They are, though, very similar to (hopefully the better) of many images you can find on the web and in published books. Not exactly the same of course: light always varies:

But the thing is I was adding no new knowledge—I was just applying technique at good locations and getting good images of increasingly famous views. This was no kind of personal artistic response to land I knew well. I’m not saying that well known views can’t make good photos. If I lived in Slovenia, and visited the site of Sveti Tomaž nad Praprotnim at dawn on a regular basis, got to understand the local environment and the weather and the history, and produced a series of images some of which might be very similar to the ones I actually took, it would be different. But as it was it was just travel photography.

I have nothing against travel photography. I will always do it. But I guess I’m saying that travel photography of landscape is not landscape photography. Landscape photography requires a connection to the land. That doesn’t mean you have to live there, but it does mean you can’t just be a tourist. But where I live, and also Tasmania and parts of New Zealand: this is where I understand the landscape.

Is there a photographer which has influenced you?

David: Of course many. The landscape photography of Fay Godwin, the British landscape photographer whose representative publication Land is probably the biggest influence on my landscape work in early days, or maybe my thinking about landscape work — my images don’t look much influenced by her, somehow. She’s not a photographer’s photographer—they are medium format film images, technically fine, but not with the crisp balance of composition and contrasty gradation of say the West Coast school in the US. Yet somehow they have a poetic quality that speaks of her subjects better than many a more dramatic image.

Kyōichi Sawada is probably the photojournalist whose work most speaks to me. Astonishing work, much greater than that of many a celebrated war photographer.

Talking of the West Coast style, when very young I loved Adams and bought and read all his work on film technique, devising complicated ways to use the Zone System with 35mm film. I no longer love the work: whether there is something about those images that is a trifle cold, or whether through no fault of its own it’s become degraded by over exposure and the production of too many prints and merchandise I don’t know. But you asked about influence, not what I like. And it’s certain that that early exposure to Adams and the technical work that arose from has probably helped shape an approach to technique that owes a lot to that school.

Are there any features that you especially care about in a lens?

David: There a range of different characteristics I look for in a lens, depending on the purpose of the lens.

For landscape, especially when hiking is involved, I prefer:

(1) Manual helicoids for haptics and to keep focus in place

(2) 10 or 12 straight aperture blades (which produce the kind of sunstar effect I prefer – although the hybrid system on the new CV 2/50 is promising)

(3) Relatively compact design – which means accepting slower apertures.

(4) Hight contrast, low glare with the light source in the frame (can accept a few artifacts

(5) Ideally sharp across the frame by f5.6; 6.3 will do. If it doesn’t get evenly sharp until f8 you are losing a little to diffraction.

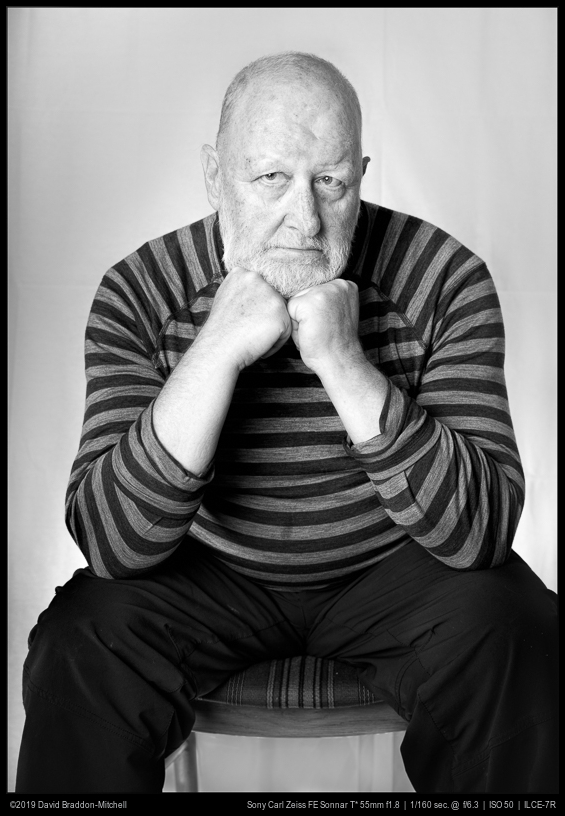

For portrait work:

(1) Fast eye-AF

(2) Smooth bokeh with minimal outlining at open aperture

(3) 11, 13 or 15 curved aperture blades.

(4) Decent speed: the wider it is, the more useful speed is. At 35mm f1.2 is actually useful, and I like it to be at least f1.4. At 50mm f1.4 is nice, but f1.8 will do. At 100mm f2 is plenty. (not that a 1.4/100 or 1.4/85 wouldn’t be fun, it’s just not a priority for me)

(5) Size is less of a priority than in the landscape kit. Though I really, really wish that it was possible to make something like the Sigma 1.2/35 a bit smaller and lighter!

And of course there are different criteria again for travel: here I might want some AF lenses, but not too heavy, so the Batis 1.8/85 and FE 1.8/55 often go with me because they are a bit smaller than some lenses but not huge.

And, finally, it’s still fun to use older vintage lenses for the look their aberrations provide. The Zeiss C-Sonnar is a nice compromise which gives you most of what is good about older Sonnar type designs, in a better performing package:

In all of this I (as I think we all do at this site) value build. Not really because the lenses will last—it’s very hard to predict that from apparent build quality—but because we are all basically amateurs who sell only the occasional picture for fun rather than for a living, and photography is more fun if the build of the gear you are using is good. If you were primarily an artist using photography as a medium you might not care, and if you are a professional it’s all about what gets the job done in a cost effective way.

Do you have a favorite lens at the moment?

David: I’m using the Loxia 2.4/25 a lot at the moment. But favourite lenses are ephemeral. They are just the best of the current crop that I am using. I tend to use lens choice in part as a deliberate straightjacket. When I’m not engaging in a special project, when the project dictates the lens, I’ll often pick a lens or a couple and confine myself to them, trying to find images that speak to their strengths. It’s a way of providing scaffolding or structure around my work.

What’s your best image?

David: I really can’t answer that. I just have no idea. There are some I love for the memories, others for a whole range of different reasons I can’t compare. Some I’m proud of technically (300 frame stacked botanical macro images for example) that look cool, but who knows:

But let me just use one landscape image, which reminds me of one of my favourite places in New Zealand where I lived for a while, even if I couldn’t say it’s a “best” image:

Can you suggest a lens we should review?

David: I think when Juriaan was interviewed he recommended the Voigtländer 2/50 Apo Lanthar. I concur—I was kind of hoping my copy would arrive first so I could review it! Phillip has it, so we will see a review from him first, to which I may contribute. I’m very excited about it, as it’s exactly the kind of lens I’ve long wanted a set of. Impeccable, not too fast (because speed either increases size and weight or decreases quality. You can have fast, great and large, or fast small and less good.) The Loxia 2.4/25 is my favourite so far in this genre. If the Voigtländer is as good as we hope then it’ll be part of a nice, small set, and replace the Loxia 2/50 in my small manual kit.

Where can people see more of your photographs?

If you want to see more of my pictures you can follow me on Flickr.

David Braddon-Mitchell

Latest posts by David Braddon-Mitchell (see all)

- Laowa FFii 90mm F2.8 CA-Dreamer Macro 2x: getting close! - August 21, 2022

- FLM Ballheads: a rediscovery - February 4, 2021

- Laowa 14mm f4 Detailed Review - December 31, 2020

great read, always interesting getting to know contributers to this blog better.

In my eyes David has quite a different style to the others on the blog, i find this refreshing and enjoy reading his reviews very much.

He is also the only native speaker, always keeping an eye on our articles with regards to grammar and spelling 🙂

Do like the intro!

Not sure about anything…, but we make up stories…, and often take them for facts.

So someone who says I’m not sure, I do not know, knows at least he does not know.

It makes me feel more comfortable!

Thank You

Nescio

Hi David.

Thank you for your work.

Your Zuiko 50/1.2 article was the best available source of information on this piece of glass.

Ultimately my quest of finding lightweight 50/1.2 ended with Canon FDn, but 285g from Olympus sure was (and is) a temptation.

Thanks.

I (DaveFP) pay particular attention to David’s posts on FM.

I really connect with his comments regarding gear as they speak to images/imaging rather than the minutia we all tend to get caught up in.

Wonderful article that allowed me to get to know him as a photographer.

Well done; another great article on a great site !

Thanks, other David!

So I work for a very conservative company in the US that does not allow NSFW content at work. I often read photography blogs on my work breaks. This site is approved through our company content filter as a “safe for work.” (this will probably change after today)

I have no problem with the content of this page, but I would not have opened this page if it had been tagged as NSFW in the title from my rss feed. Not warning some users could cause problems for them in their personal lives. If my employer goes through the images in this blog this could cause me problems at work. I had to per-emptivly notify my HR department that I accessed this page without knowledge that it contained unclothed women. Thank you for forcing me to have this moment with my employer. This site will probably be blocked for me moving forward. Please, consider some of us living under religious oppression when you post images like this.

You mean the figure images? They would count as unacceptable at your workplace?? So Edward Weston would count as “not safe for work”? Wow. I’m not disbelieving you, just surprised. I guess we are a bit out of touch with how things are in the States these days. What could we do to help you in this kind of situation?

from what he writes, i don’t think anyone can help him. “If my employer goes through the images in this blog” “living under religious oppression” sorry but seriously, wtf?

It sounds like contrived nonsense.

I doubt any reasonable employer would think twice about those images. Even if his anxieties are well founded, it seems posting this comment may give more offense to his boss than figurative art would haha

Good to know you. I hope the wildfire end soon.

So do we. 3000 homes destroyed (ours was threatened at one point) and area the size of England burned. An absolutely unprecedented blaze, but unless something is done, it’ll happen again.

Fundamental reason would be the climate change. I never agree more about preventive actions before the disaster. Have a good night (Yes, I’m in the similar time zone!). I really pray for that.

Exactly!

Fantastic article! I love seeing your style – black and white is a wonderful tradition that I don’t see a lot of photographers continuing recently. I especially love your figurative work and your interest in the human form. It’s good to see this represented on the blog.

Thank you, David Braddon-Mitchell, for an intriguing, honest and straightforward perspective on your photography and what turns your crank when indulging your passion. Please allow me to echo the others who sent their blessings to you and all of your Australian friends; I hope that the worst of this year’s wildfires is over.

PS: I’m still loving the Batis 135mm F/2.8. I only wish that, like you, I could afford the A7R IV… we’ve been renovating the house, so a little short at the moment.